The big shift I see in horticulture over the next decade is a shift from thinking about plants as individual objects to thinking about plants as social networks--that is, communities of compatible species interwoven in dense mosaics. The advantages of this approach are huge (particularly with green infrastructure), but the challenge is that it is hard to do. Part of the difficulty comes in not understanding how to layer plants one on top of each other; it's very different than traditional horticulture. Traditional horticulture is place-based. Plants are arranged, often in masses of the same species, based on location. So to try to clarify the idea of vertically layered planting, I want to offer a different way of thinking about plant arrangement: modularity. So in this post, I'm offering a slide show (above) to explain how to use the idea of modularity as a tool for certain types of planting applications.

MODULARITY IN DESIGN

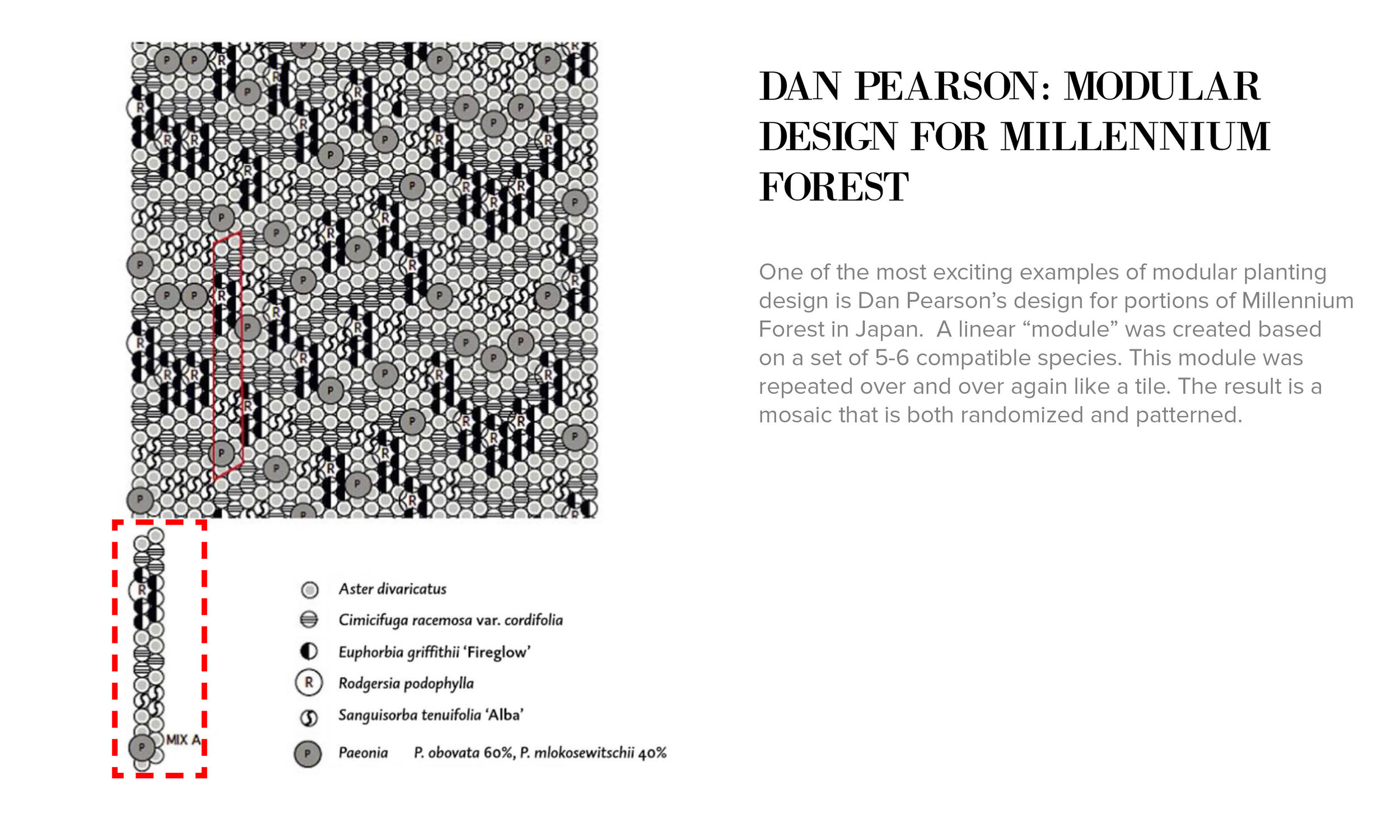

The concept of modularity has driven innovation in design since well before the industrial revolution. Modular design seeks to create discrete scalable, reusable units that can be separated and recombined. The number of resulting combinations are endless. Modular design combines the best aspects of standardization with customization.

Modularity also works in natural systems. In biology, modularity refers to the ability of a system to organize discrete, individual units that can overall increase the efficiency of the network. Modularity is observed in all systems, and can be studied at nearly every scale of biological organization, from molecular interactions all the way up to the whole organism.

PLANT POPULATION DISPERSION PATTERNS

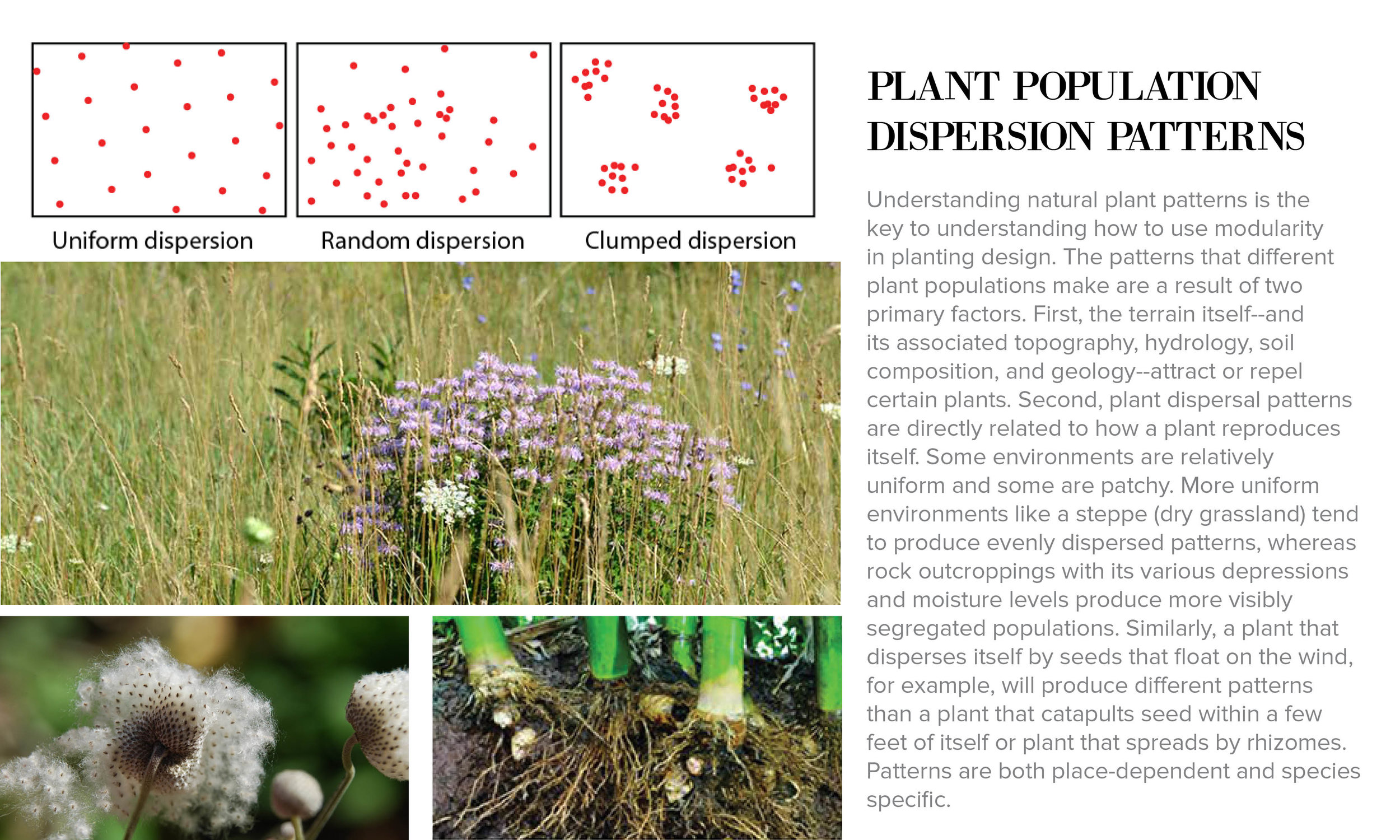

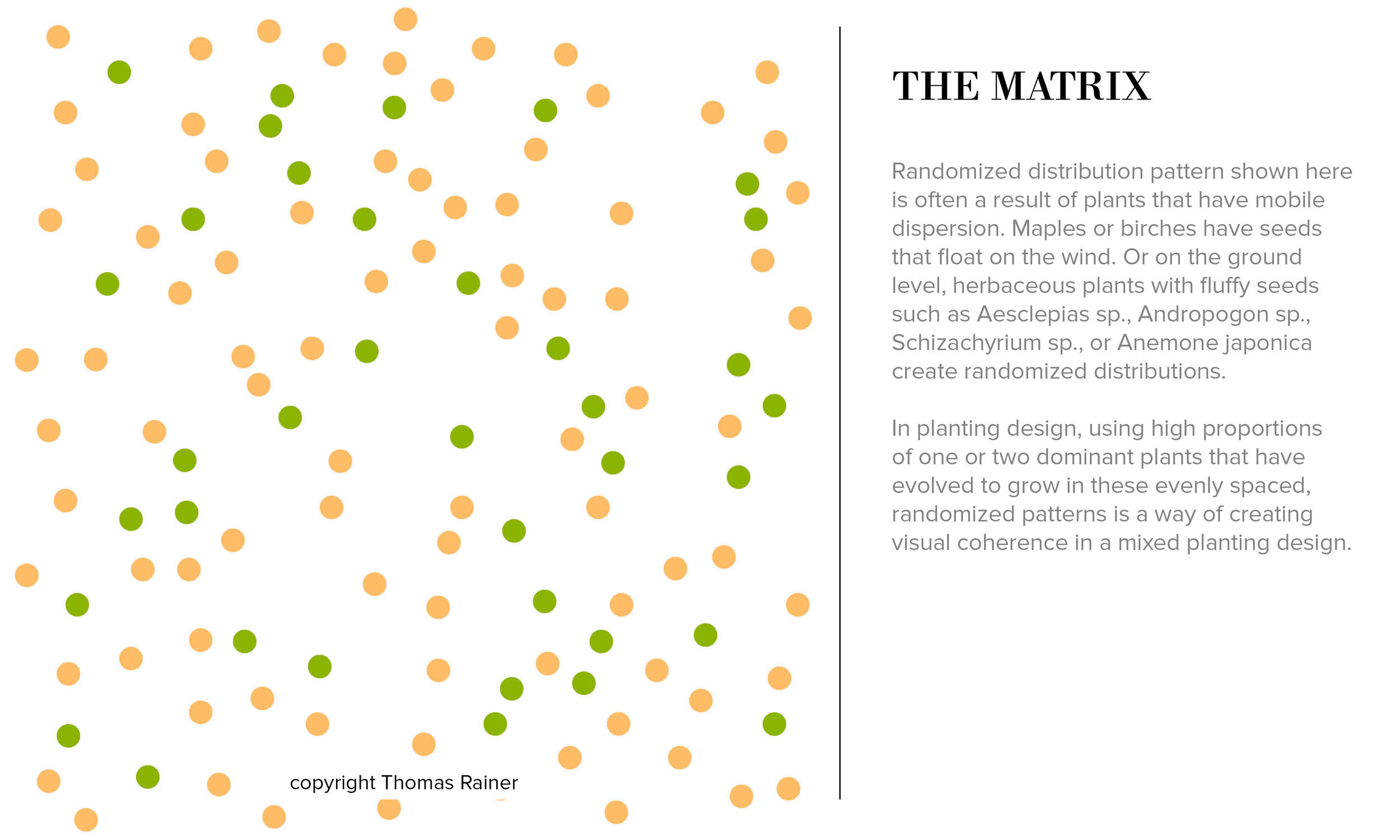

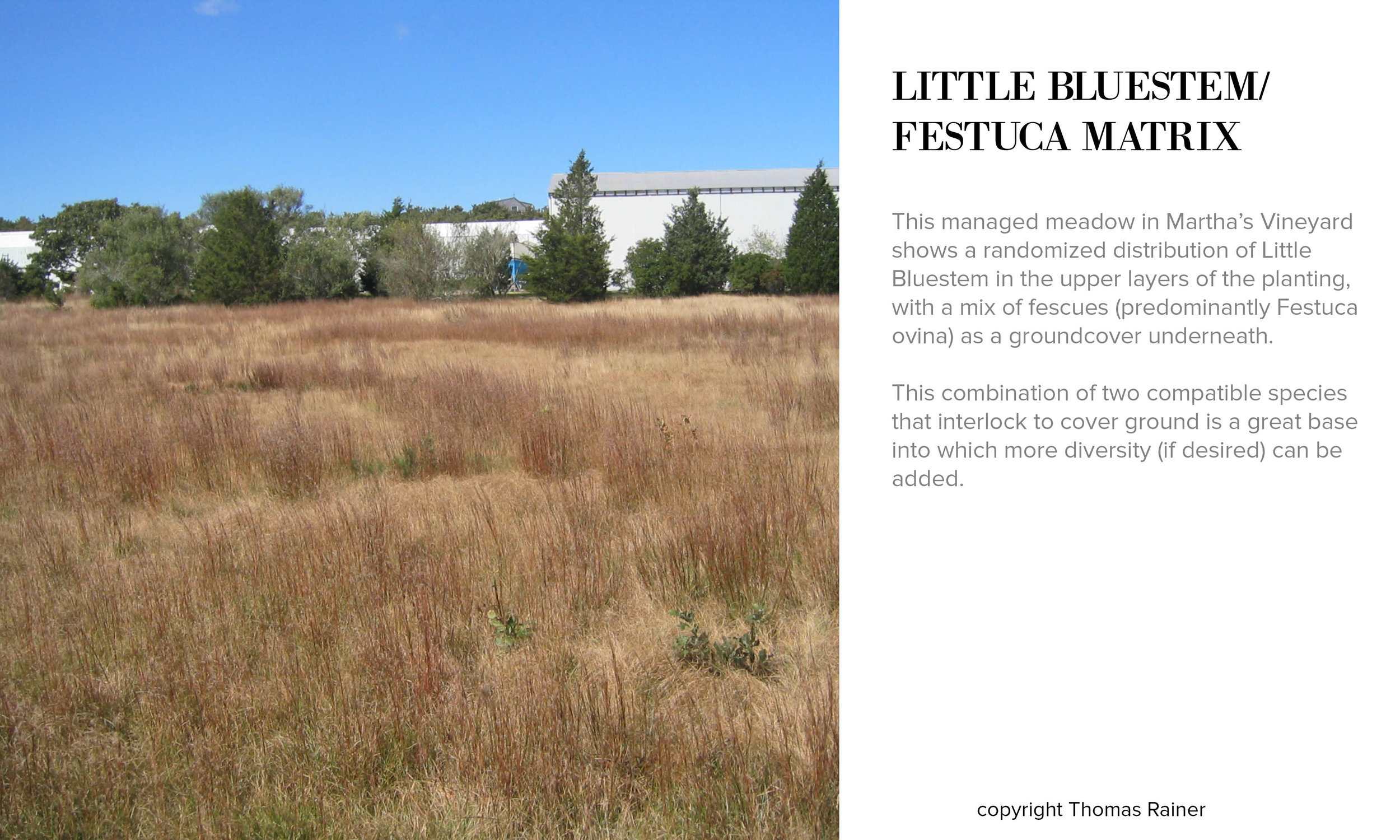

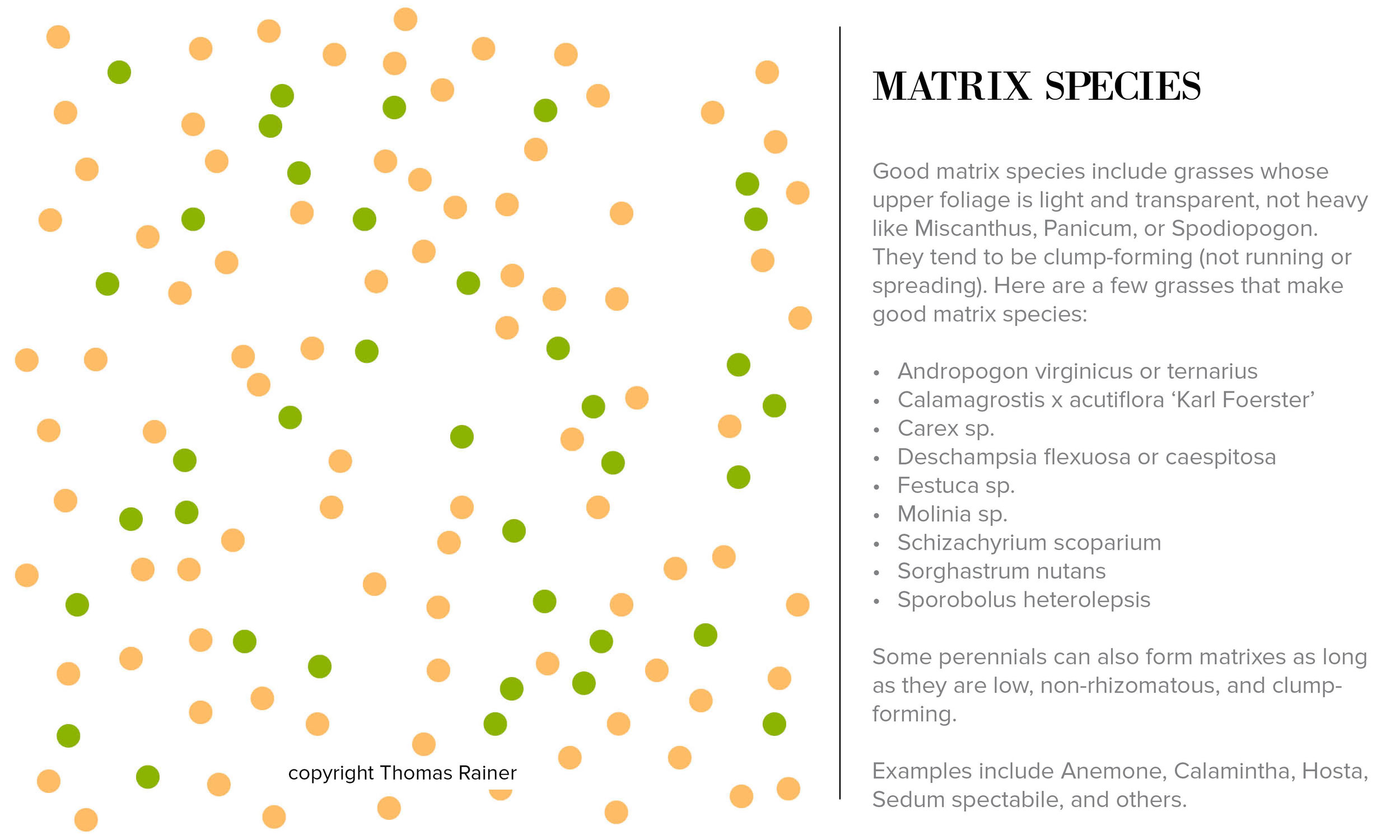

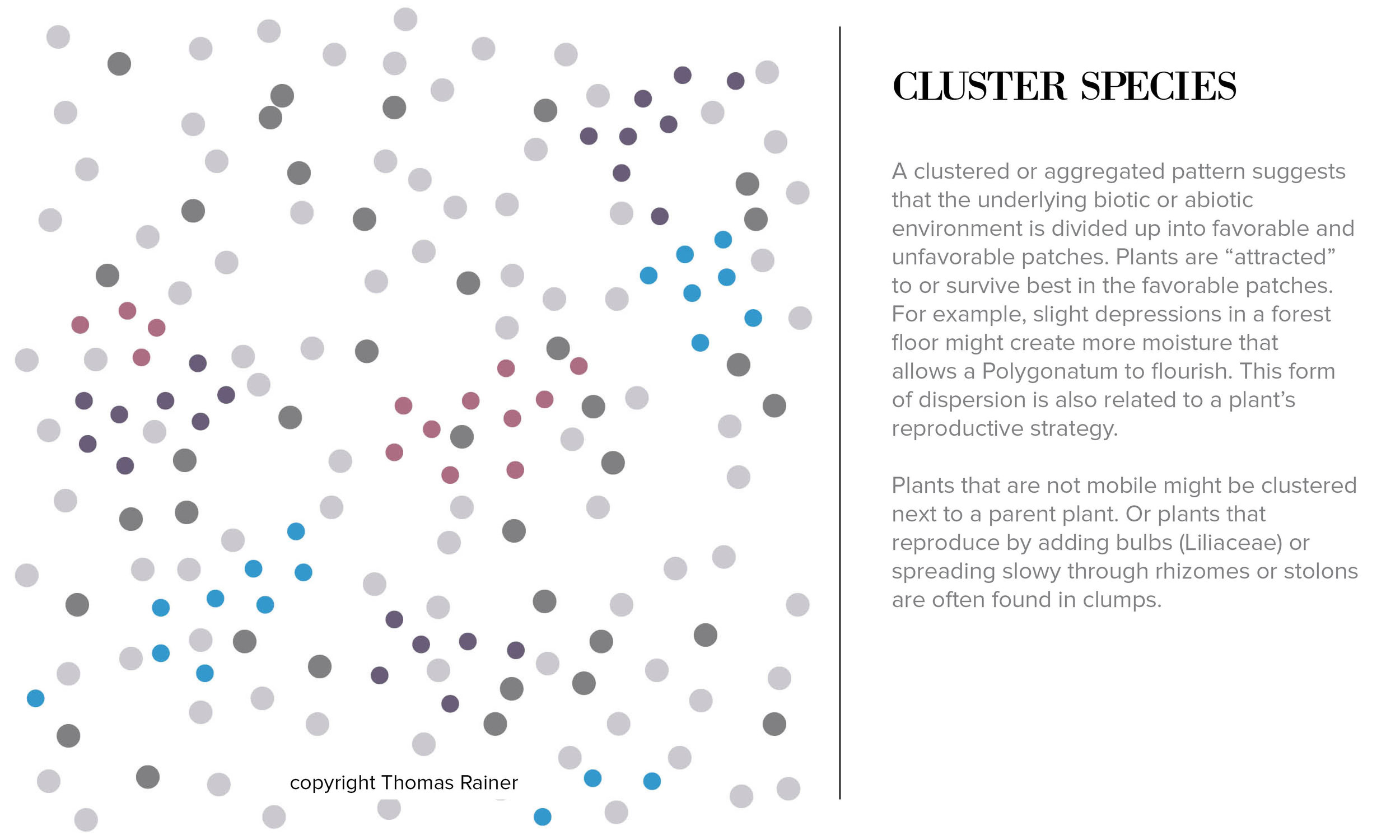

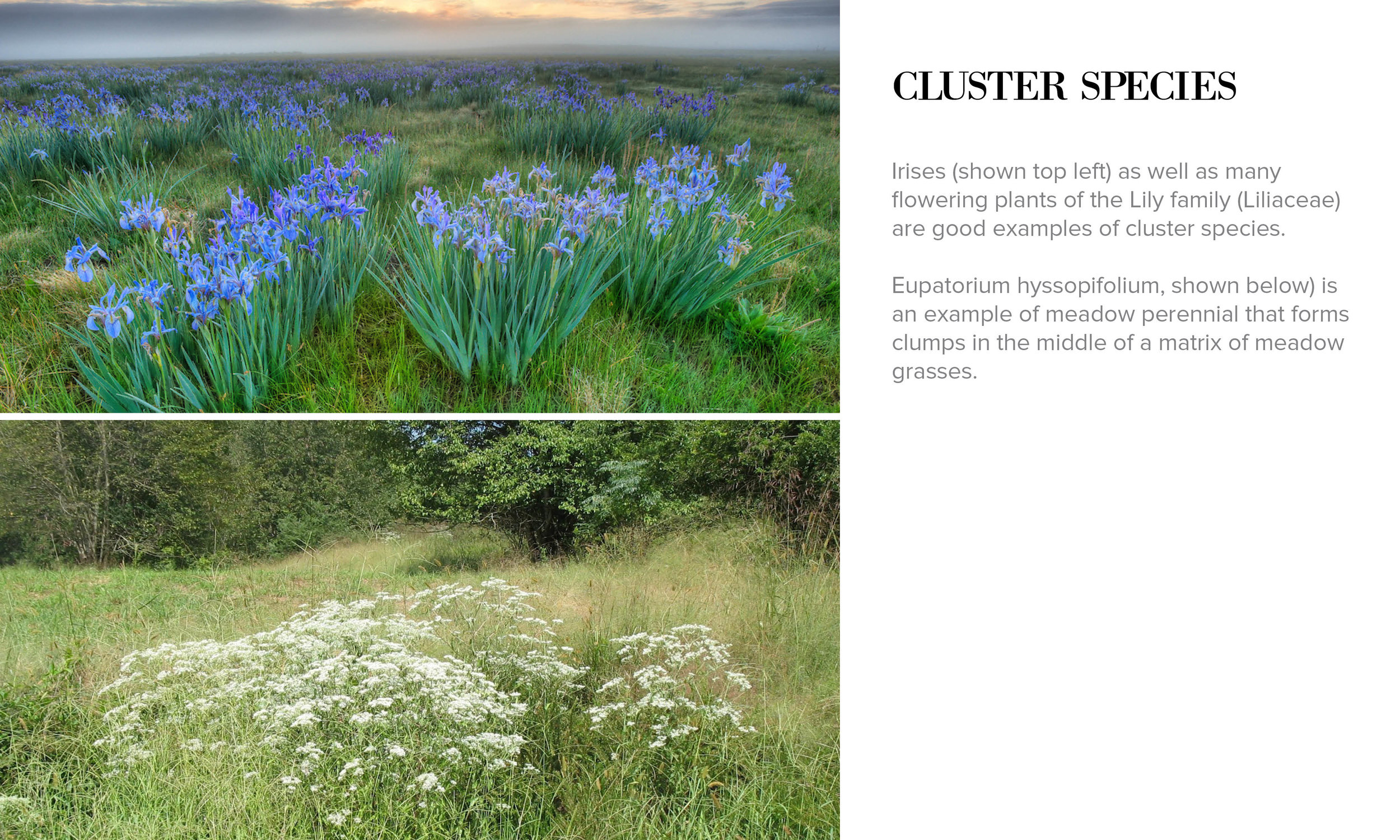

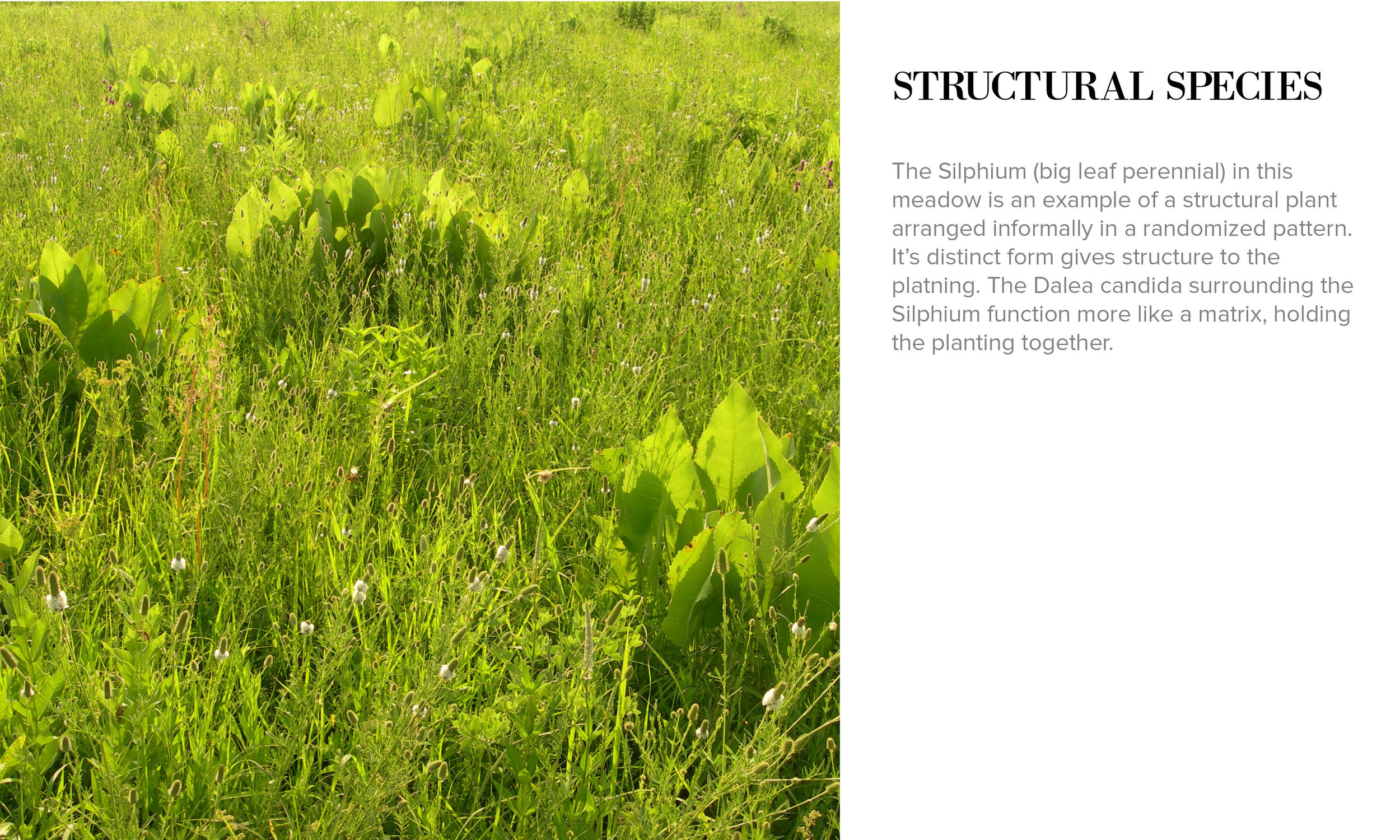

Understanding natural plant patterns is the key to understanding how to use modularity in planting design. The patterns that different plant populations make are a result of two primary factors. First, the terrain itself--and its associated topography, hydrology, soil composition, and geology--attract or repel certain plants. Second, plant dispersal patterns are directly related to how a plant reproduces itself. Some environments are relatively uniform and some are patchy. More uniform environments like a steppe (dry grassland) tend to produce evenly dispersed patterns, whereas rock outcroppings with its various depressions and moisture levels produce more visibly segregated populations. Similarly, a plant that disperses itself by seeds that float on the wind, for example, will produce different patterns than a plant that catapults seed within a few feet of itself or plant that spreads by rhizomes. Patterns are both place-dependent and species specific.

DESIGN OPPORTUNITY

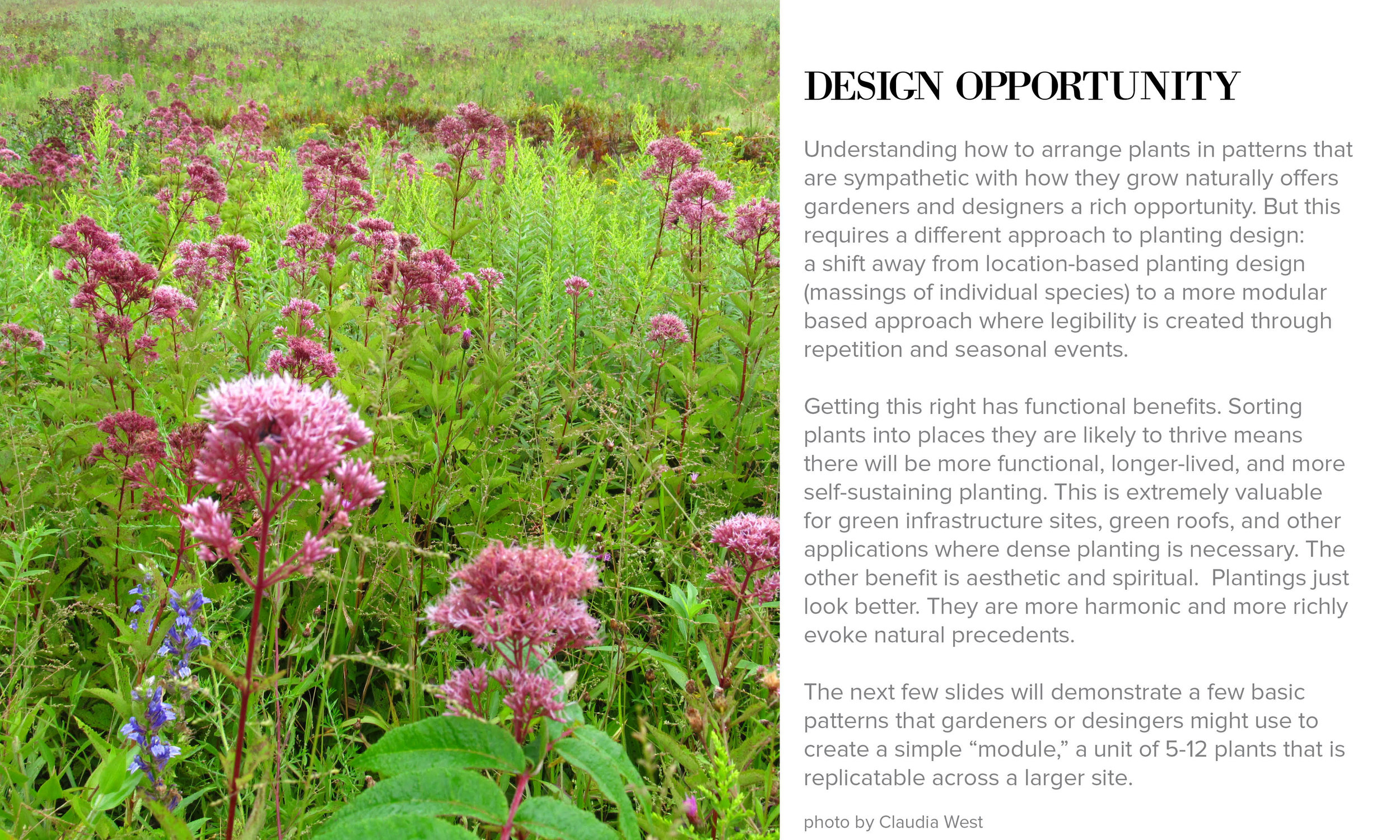

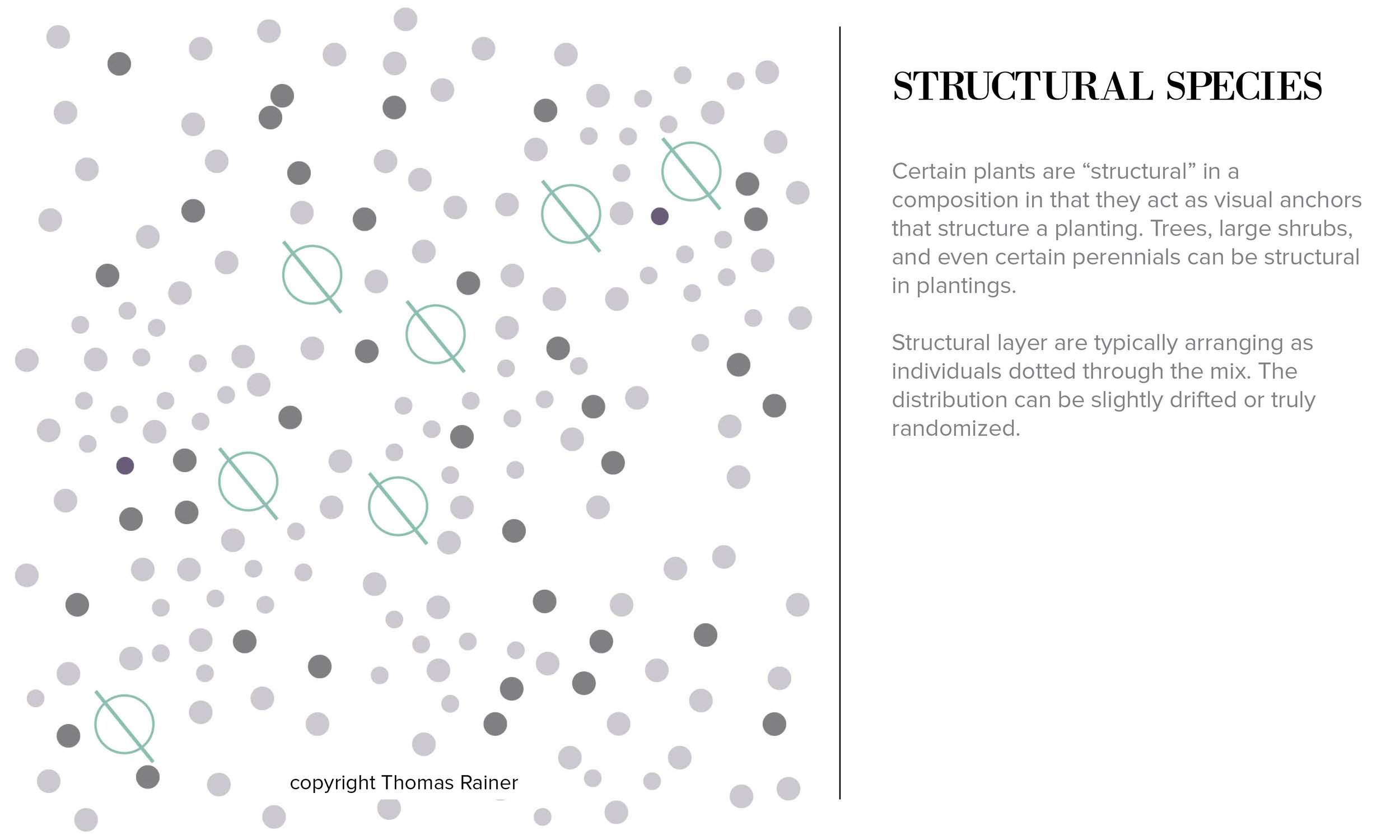

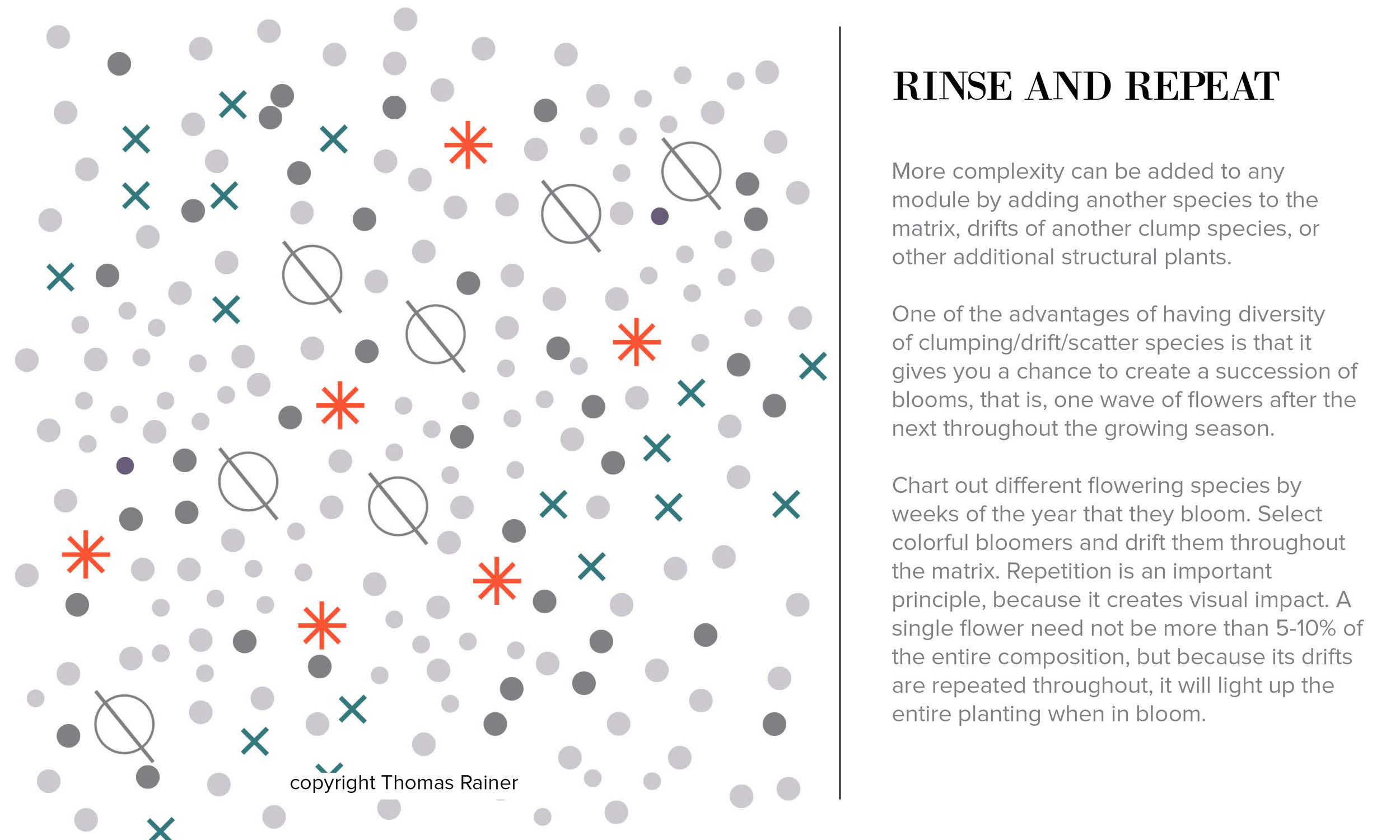

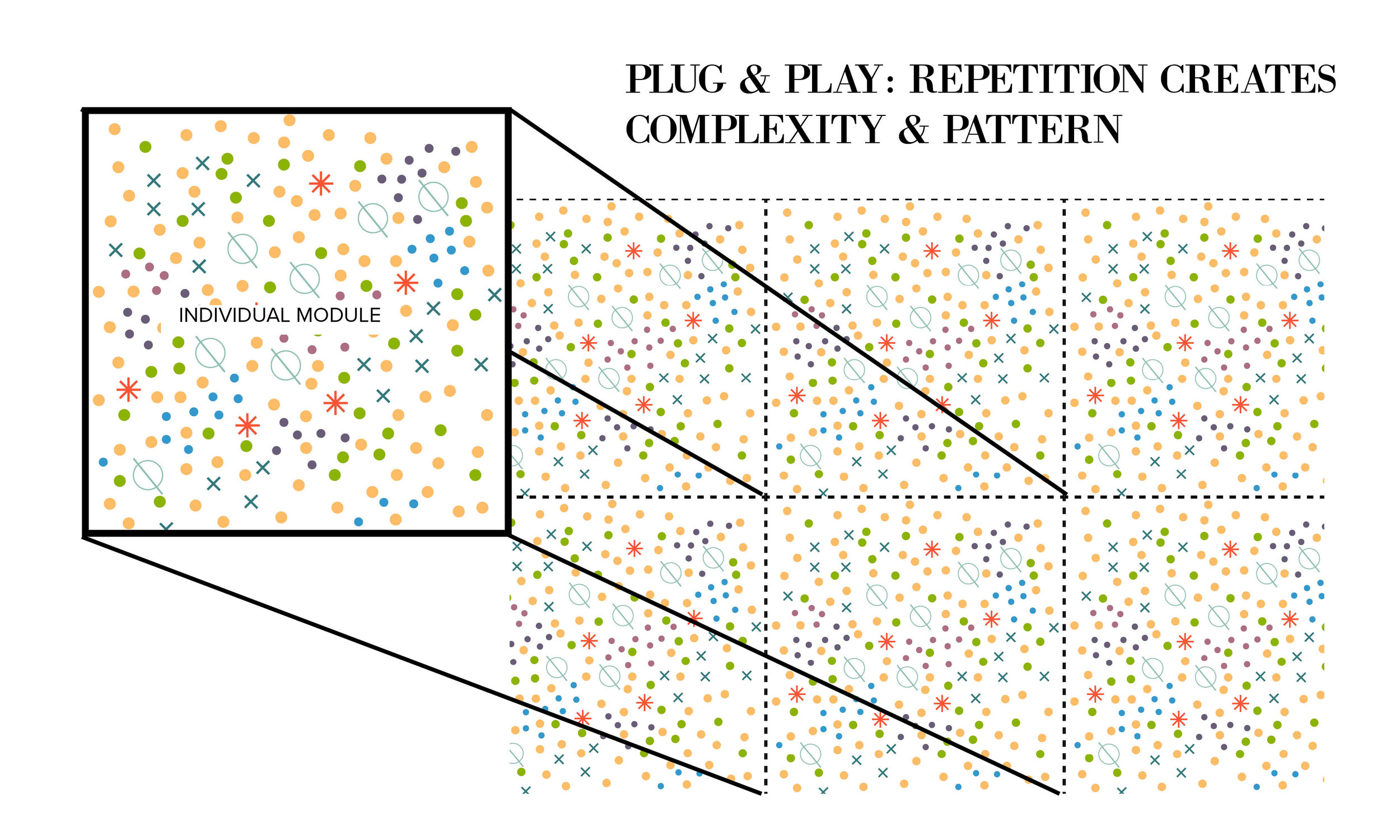

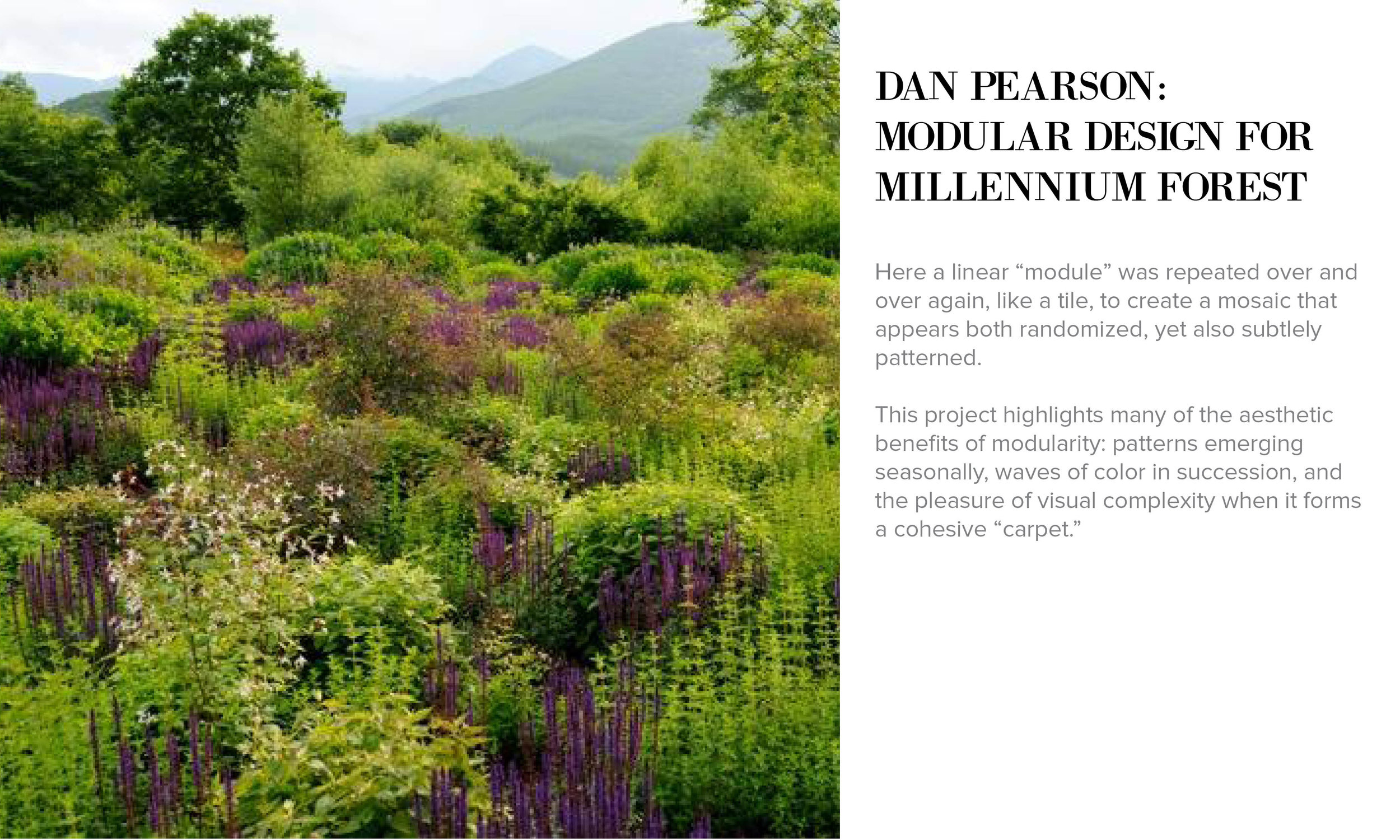

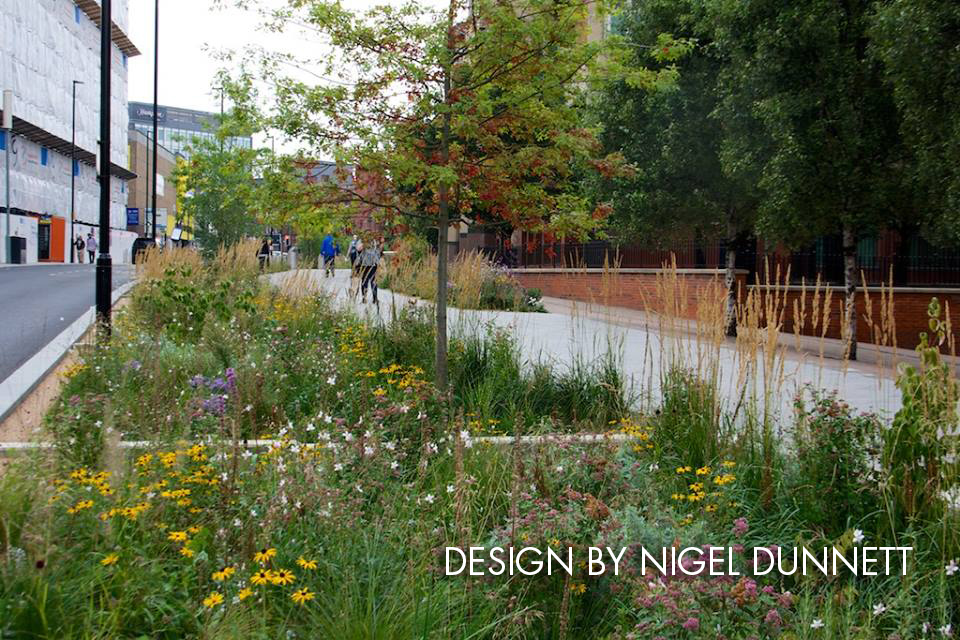

Understanding how to arrange plants in patterns that are sympathetic with how they grow naturally offers gardeners and designers a rich opportunity. But this requires a different approach to planting design: a shift away from location-based planting design (massings of individual species) to a more modular based approach where legibility is created through repetition and seasonal events.

Getting this right has functional benefits. Sorting plants into places they are likely to thrive means there will be more functional, longer-lived, and more self-sustaining planting. This is extremely valuable for green infrastructure sites, green roofs, and other applications where dense planting is necessary. The other benefit is aesthetic and spiritual. Plantings just look better. They are more harmonic and more richly evoke natural precedents.

The slides above demonstrate a few basic patterns that gardeners or designers might use to create a simple “module,” a unit of 5-12 plants that can be replicated across a larger site.